WASHINGTON — As the nation commemorates the 250th anniversary of the beginning of the Revolutionary War in April, the Army looks back at the roots of its legacy of service.

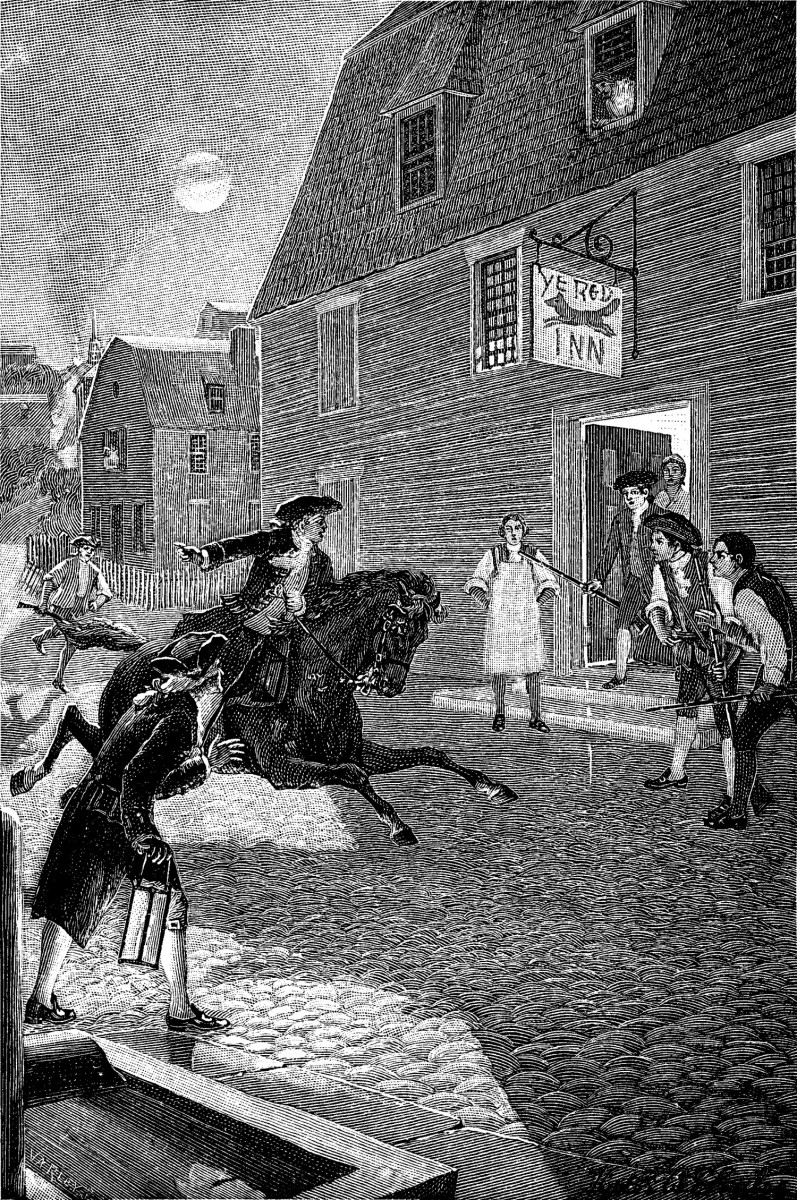

Paul Revere and his midnight ride is one of the most recognized images from the events surrounding the battles at Lexington and Concord on April 19, 1775. While most people think of him as a lone actor, he was part of a much larger network of early warning intelligence systems and communication nodes the Army later developed into the Signal Corps and military intelligence.

The crisis that led Paul Revere on his famous midnight ride didn’t begin overnight.

Resistance Groups

When Britain began to place more financial burdens on the colonists in the 1760s and remove fundamental rights, many colonists began to organize resistance groups like the Sons of Liberty.

By 1774, Massachusetts was the focal point for civil unrest, and the British government took extreme measures against the colony. The Crown curtailed most civil liberties, closed the port of Boston, and in October, dissolved the colonial legislature.

In response, the legislature continued to meet as the representatives of the people, calling itself the Massachusetts Provincial Congress. Working through the Fall, the Provincial Congress established a Committee of Safety, reorganized the colony’s militia, encouraged more efficient leadership, and established higher standards of readiness for quick-reaction units, known as minute battalions. Soldiers in these units tended to be younger, more highly motivated, better trained, and were known as “minutemen.”

Most minute units were led by combat veterans of the French and Indian War (1754-1763). By early 1775, nearly 20,000 troops were organized in militia regiments and minute battalions across the colony.

Secret caches

To support the combat element of what was being referred to as the Massachusetts Provincial Army, the Congress established a Committee of Supplies to amass military stores and equipment in secret caches around the colony.

Communities hid small arms, ammunition, artillery pieces, tents, entrenching tools, medical chests, and other supplies in gardens, outbuildings, and basements. If the growing force of 4,000 British regulars in Boston were ever to begin a conflict in Massachusetts, the Provincial Army would need these supplies to rapidly mass and meet them in combat.

Since the citizen-soldiers of the militia could not stay on alert permanently, the provincials organized a robust intelligence and signal network to provide early warning if a threat appeared.

Intelligence agents inside Boston collected information on British plans and speedily sent word into the countryside so that the Provincial Army were almost as informed of the actions of the British military as the British were themselves.

The Committee of Safety established a network of alarm riders in the counties around Boston to be able to rapidly spread the word should the Sons of Liberty have actionable intelligence.

Paul Revere

An early member of the Sons of Liberty who had experience carrying urgent messages across the colonies was 40-year-old silversmith Paul Revere.

By April of 1775, he was one of those in Boston entrusted with the mission of passing through British lines to carry word into the countryside should the regulars ever march on a provincial target. If caught with incriminating information, Revere and the other alarm rides could suffer imprisonment or death.

On the evening of April 18, patriot leader Joseph Warren received intelligence that a force of about 700 redcoats was assembling to march west toward Concord the next day to seize military supplies and arrest members of the Provincial Congress.

Warren instructed Paul Revere and William Dawes to escape the city and activate the colony’s alarm network.

Unsure if the British force would march out via Boston neck or ferry their troops across the Charles River toward Cambridge, Revere coordinated signal lanterns in the steeple of Boston’s Old North Church: one if by the land route, two if by water.

This simple but effective code let Revere and other alarm riders know just before midnight that Royal Navy sailors were ferrying the regulars to Lechmere Point.

Revere slipped past the warships in Boston harbor to Charlestown, where he mounted his horse and raced westwards to spread the alarm.

Joined by William Dawes, who had spread the alert on the route from Boston Neck, Revere rode through the night toward Concord, spreading word that, “The regulars are coming out!” This triggered the colony’s alarm network.

Alert riders spread the word north, west, and south, with word reaching as far away as New Hampshire, Maine, and Rhode Island by the end of the day on April 19.

The network activated some 14,000 militia and minutemen in 47 regiments all within marching distance of Concord.

Church bells and drums called the soldiers to muster, families cooked rations and rolled cartridges, and dozens of companies began their march.

Few thought it would be the first action in what would become an eight-year war for independence, nor that someday an organization called the U.S. Army would develop signal network systems based on relays to communicate across the battlefield. The groundwork established in colonial Massachusetts forms the basis for the modern-day Army Signal Corps and military intelligence branches.

This "Paul Revere’s ride pioneers Army signal corps, military intelligence" was originally found on https://www.army.mil/rss/static/380.xml